One billion people, or 15% of the world’s population, experience some form of disability, and disability prevalence is higher in developing countries.

Well planned infrastructure and inclusive urban services are fundamental to unlocking the potential of people with disabilities. Currently, DI is not consistently addressed across DFID’s infrastructure programming and policy dialogue. It is not always clear to DFID staff or partners what DI means in relation to infrastructure and growth [1], and the actions they might take to achieve it. This is coupled with a perception that addressing disability in infrastructure programming is prohibitively expensive and often unaffordable within project or programme budgets.

This case study highlights the opportunity for DFID urban growth, infrastructure and transport programmes to build disability inclusion into programming activities, using examples from the delivery of Dar es Salaam’s Bus Rapid Transit system, Tanzania.

The Programme

Construction of the first phase of Dar es Salaam’s Area Rapid Transit (DART) was completed in December 2015 at a total cost of €134 million funded by the African Development Bank, World Bank and the Government of Tanzania. The first phase commenced operations in 2016, with a total length of 21 kilometres with dedicated bus lanes on three trunk routes with a total of 29 stations. The DART system provides rapid transit for 160,000 passengers a day [2] and provides a good practice example of disability inclusive design for a transport infrastructure project.

The Approach

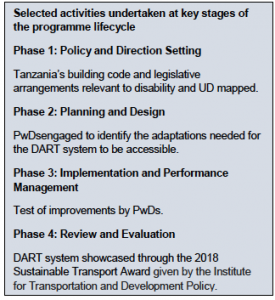

During the initial design phase, UD standards were adhered to such that disability access was mainstreamed through the design. Near to completion, a civil society group called the Comprehensive Community Based Rehabilitation in Tanzania (CCBRT) Advocacy Unit was engaged to understand the detailed needs of passengers with disabilities. In early 2016, the unit partnered with DART to ensure the public bus system was safe and accessible for PwDs. To assess this service, members of the advocacy team including people with hearing and visual impairments and physical disabilities tested the stations and rode on DART buses throughout the city. [3]

Their travel experience was positive overall, and they shared recommendations for improvements, such as installing a lower ticket window for people in wheelchairs, adding disability awareness signs in Kiswahili, and including braille on tickets. After DART’s launch in May 2016, the Advocacy Unit visited the project again to test improvements and help an awareness raising campaign to inform PwDs about the new service. The awareness raising campaign was disseminated through normal media channels as well as through the CCBRT communications to their members with disabilities, which helped reach those who may struggle to access television, radio, internet, newspapers and billboard posters.

Outcomes

DART has reduced commute times by more than half for some residents, who previously faced upwards of four hours stuck in traffic every day. [4] It is being hailed as a success story for sub-Saharan urban transport and has recently won the 2018 Sustainable Transport Award given by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP).

However, accessibility is not universally included in BRT schemes. For example, in Lagos, Nigeria, even basic requirements for accessibility such as access ramps and handrails have been omitted. As a result, the system is unusable for many PwDs who would have benefited from an inclusive design process. [5]

References:

[1] Results of ICED survey; report

[2] Source: https://brtdata.org/location/africa/tanzania/dar_es_salaam

[3] Source: http://bit.ly/2MrIrtO

[5] Source: Frye, A. (2013) Disabled and Older Persons and Sustainable Urban Mobility. Thematic study prepared for Global Report on Human Settlements 2013 Available from: http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2013